I’d always meant to learn to code, but there never seemed to be a good time.

I graduated in 1996 with a degree in archaeology and got a well-paid job as a management trainee. I zoomed up the corporate ladder, doing what I thought successful people did: getting promoted and joining a prestigious management consultancy — until I realized that writing PowerPoint slides for sixteen hours a day and saving giant corporations millions on their stationery budgets was all a load of nonsense.

Instead, I wanted to do something meaningful and skilled and — gasp — fun. So in 2003, I co-founded a book publishing company called Snowbooks with my best friend. What could be more important, more deserving of effort, than books?

It wasn’t a particularly brave move. I reasoned that if Snowbooks failed outright, the worst case scenario would be that I’d just get another of the same sort of awful job I was already stuck in.

Thankfully, it’s been a superb ride — and I’ve learned lots of things along the way.

You might also like: An Overview of Liquid: Shopify's Templating Language

Innovation is easier when you don’t know how things are meant to work

Building Snowbooks gave me a chance to dabble with technology as well as explore the creative aspect of the business.

From the start, we used XML to automate the creation of our marketing materials in InDesign. We used off-the-shelf packages such as Microsoft Access and Filemaker to write little database programs to keep our data in order, to calculate our royalties and to keep track of our sales.

I didn’t know anything about publishing before starting the company — which made innovating a lot easier. Whilst my programming capabilities stopped abruptly at the ‘hobbyist’ level, our business focus and innovations won us awards and a pretty high profile in the industry.

Disasters often have silver linings

And then, disaster struck. 2010 was the year from hell, which brought a series of personal and business crises. By the end of it, I had little money, and my trust in human nature was completely shattered.

At last, the time had come to learn to code. It was the perfect antidote to my personal crisis.

Looking back, coding was just the sort of logical, immersive, rewarding activity I needed to focus my mind, regain my self-belief and give me something to work towards.

Ruby on Rails rocks

I needed to build some sort of new system to allow me to store all my Snowbooks data — by this time, there was a lot of it, and it wasn’t very well organized.

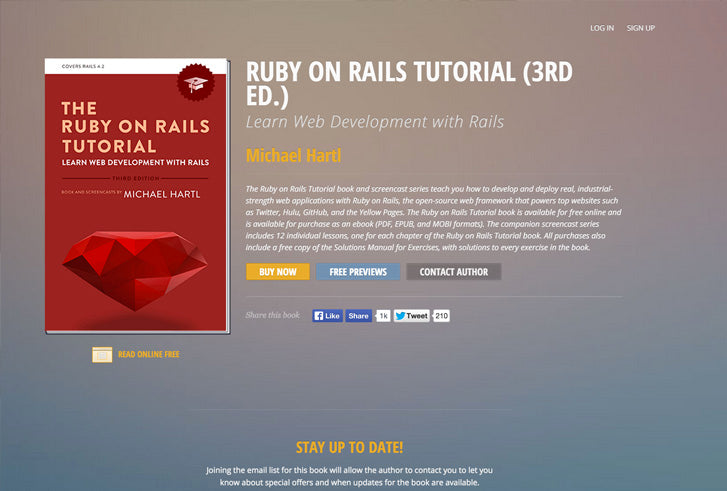

I remember my best friend recommending Michael Hartl’s The Rails Tutorial as a gentle but thorough introduction to the web development framework Ruby on Rails. Later that day, I sat on the sofa, laptop at the ready, tutorial book in hand — and all my cares slipped away. This magical, open-source way to create significant, functional websites out of thin air, just by typing into a text editor, blew my mind. I was hooked from the start.

Learning to code takes time, but holy smokes, it’s worth it

Days passed, and I got to grips with the basics of Ruby, databases and HTTP. Weeks passed, and I finished The Rails Tutorial. By following its instructions, I’d recreated my own version of Twitter, with my own hands!

Months passed, and I started to apply what I’d learned to build a book data management application. First, I tackled title metadata, and then contacts. Contracts, rights and royalties came next, then production management, sales and workflow. I called my application Bibliocloud — my pride and joy; my phoenix from the ashes.

Years passed, and I racked up thousands and thousands of hours of coding. Bibliocloud went through hundreds of iterations, several times being razed to the ground and rebuilt, as my skills developed and I realized there were more elegant ways to write the code. My friend and I teamed up with another developer, whose Oracle and SQL expertise brought new depths to the application.

The buzz of coding intensified as I got better. I’ve been lucky enough in life to discover several pastimes which seem to make time stand still — playing the piano, boxing, reading — but none of them match coding for its achievement highs, its need for pureness of concentration, its excruciating, frustrating, infuriating, brilliant challenge.

(No pastimes) match coding for its achievement highs, its need for pureness of concentration, its excruciating, frustrating, infuriating, brilliant challenge.

Code is easy. Knowing your industry is the hard bit.

I’d written Bibliocloud so I could run Snowbooks properly, but in 2012 other publishers started signing up to use it, too. It was almost accidental: in conversation with my publishing friends, I realized that the exact reasons I had needed a comprehensive, cheap, elegant system were shared by other publishers just like me.

By writing software that solved my real-life problems, I’d created something that had value to other publishers — something that I could turn into another business.

I have found that understanding the problem is far more important than knowing the code. Code can be learned. A real understanding of the problems of an industry only comes about when you’ve lived it.

Don’t write features: solve problems

If you’ve lived, worked and breathed the publishing industry for a while, you’ll recognize some of its problems.

For instance, you’ll know what I mean when I talk about the “spreadsheet from hell,” printed out on A3 paper in an impossibly small font, covered in pencil annotations. Every publisher without a decent system has one. Editors clutch it to their hearts as if their life depends on it. It describes their list — the books they’ll publish in the next 18 months, the dates that can’t be missed, the vital information about specs and printings. These spreadsheets are difficult to maintain, don’t interact with other systems, and everyone has a slightly different version — all of which causes chaos.

And if you’re a publisher, you’ll understand me when I talk about the strain on editorial assistants who went into publishing for the love of books, but who spend their days copying and pasting metadata into retailer spreadsheets, webforms and advance information InDesign templates, wondering where their dream went so wrong.

And if you’re a publisher, you’ll understand that being able to produce decent royalty statements isn’t a bookkeeping exercise: it’s an expression of a publisher’s regard for its authors. Lateness, inaccuracy and a lack of clarity in these statements is rightly taken as a personal slight. Authors hand over their precious words to us as a mother hands over her firstborn to a nursery. We must protect them and treat them with the utmost respect.

Systems aren’t a place to store your data. They are a means of making good on your promises and a way to nurture your relationships.

You might also like: An In-Depth Look Into Designing a Shopify Theme

Use APIs to share data between systems

You’ll also understand how delighted I was to discover Shopify last year, because until then we hadn’t solved the problem of how to provide a low cost, lightning fast, efficient, gorgeous way to carve out a home for our publishers’ books on the web.

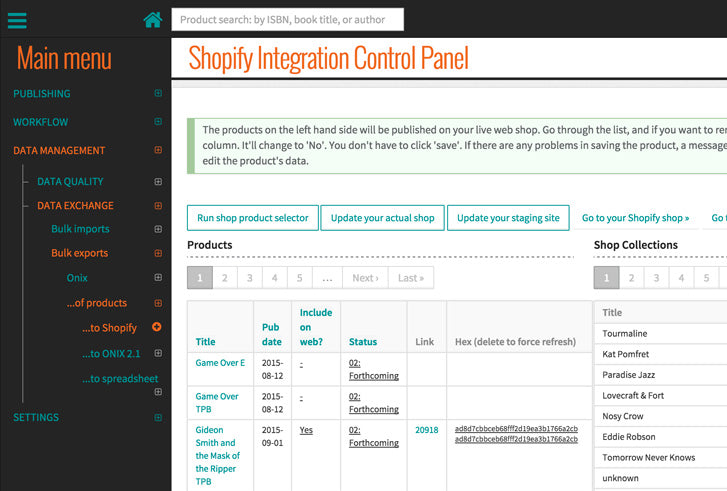

We’ve written an API between Bibliocloud and Shopify: not only can Bibliocloud now send data to retailers, wholesalers, and data aggregators in the right format, but it can feed a publisher’s own home on the web with no more effort than the click of a button to trigger the API call.

Have a look at Snowbooks.com, which is based on a tweaked version of the free Shopify Supply theme, and which takes a data feed from Bibliocloud. It uses metafields and custom collections to add publishing-relevant data such as series, publication dates, age banding, author information, and more. It also only took me a few days to configure.

Eat your own dog food

I’ve grown a publishing company from scratch, I’ve spent more than a decade immersed in the industry, and I’ve built software based on the needs of the publishing process. That’s why Bibliocloud is so popular: it’s been built to solve real problems. My Snowbooks team and I use it every day to run our own business, which keeps it relevant and sharply focused on solutions, not features.

It takes a long time to be an overnight success

And so, twelve years after I left the corporate world, Bibliocloud has just launched out of beta with customers from throughout the publishing world — academic, trade, children's, illustrated, and digital books. Our clients at launch range from start-ups with a handful of publications, to established presses with thousands of books on their backlist. Most of them will be using Shopify to showcase their wares to the world.

To the outside world, we look like a new company who’s hit the ground running and has achieved overnight success. But it would be a mistake to overlook the long journey, and our deep roots in our industry — which has been the key to our success.

I knew my industry, and the code took care of itself. The occasional disaster along the way just added fuel to the fire.

Read more

- 4 Conferences You Should Attend

- How to Collect the Right Information from Your Clients

- Learn from the Shopify Experts Who Won Build A Business

- Why Brick and Mortar Merchants Choose Shopify POS

- How to Build and Launch an Impactful Online Workshop

- 5 Ways to Help Clients Succeed in the Build A Business Competition

- 5 Practical Ways to Help Your Clients Deal With Supply Chain Issues

- Strategies for Successfully Defining and Winning Client Projects

- How to Use Your Competitive Landscape to Grow Your Agency

You might also like: 3 Essential Tips for Refactoring CSS Without Losing Your Mind